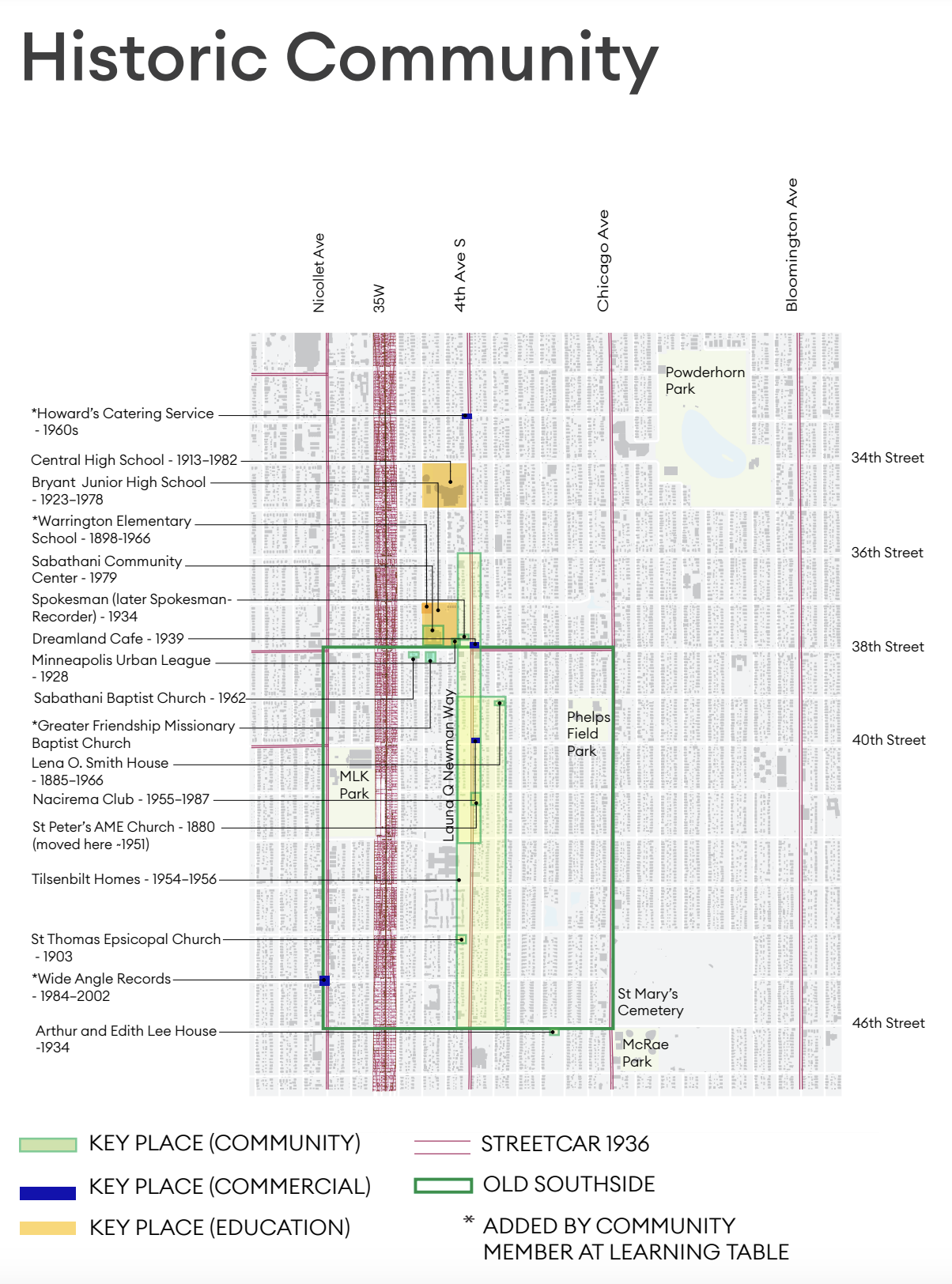

Site Context

OLD SOUTH SIDE: CULTURAL DISTRICT

Cultural District

“In August 2020, the Minneapolis City Council approved an ordinance that established eight new cultural districts in Minneapolis that fall along some of the city’s major corridors. These include 38th Street South, Cedar Ave. South, Central Ave., East Lake Street, Franklin Ave. East, West Broadway, and Lowry Ave. North. Since these areas are home to most of the city’s […]

Communities of Color who have historically been left behind, city leaders have expressed their goal in targeting these districts as waypoints for resources to be distributed equitably.

South Minneapolis was once a vibrant community of Black families, businesses, and community organizations. Between the 1930s and the 1970s there were dozens of Black-owned businesses along the 38th Street corridor, from dental offices to music venues. Many of the families living in this part of the South Side were a part of the Great Migration, when millions of Black Americans moved from the rural South to Northern urban areas in search of opportunity.”

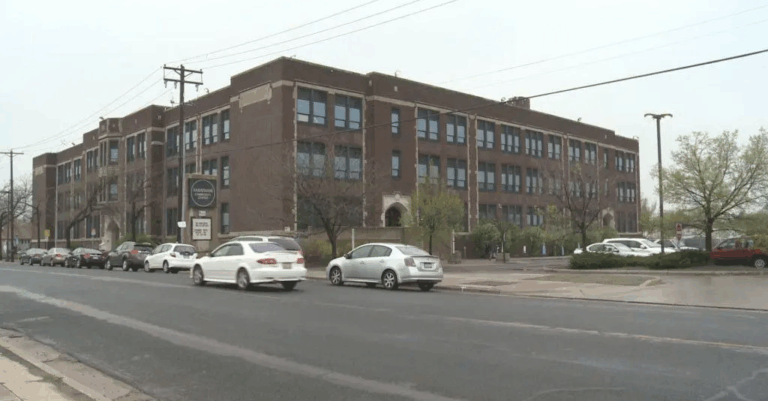

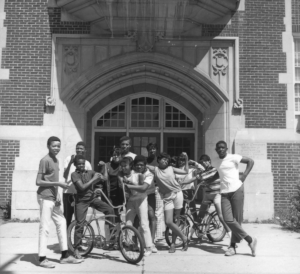

Sabathani Community Center

310 East 38th Street

“In the 1960s, Sabathani originated as a church. Back then, churches were often a “pivotal point for bringing communities together,” Anika Robbins says. Before present-day types of nonprofit organizations and community centers were created, “Churches were activism-involved and they helped push social change,” she adds.

Later Sabathani evolved into a community center at its current location, which was formerly a junior high school. It became “an avenue for children, to keep them engaged,” Robbins says.” Link

“Established in 1966, Sabathani is the only nonprofit organization founded by African American Minnesotans that is still in existence. Sabathani is located in the heart of South Minneapolis. It served 31,000 clients in 2015.

Resource Services includes one of the largest food shelves in the area. Food orders provide balanced nutrition for the entire family, including a variety of meats, legumes, rice, pasta, cereal, canned goods and packaged foods, milk, fresh fruits and vegetables (in season), baby items, toiletries, and even juice and dessert items.

Families can also get free clothing and furniture, income tax filing, back to school supplies and holiday support. Through the program, 25,000 people a year gain food security and self-sufficiency.”

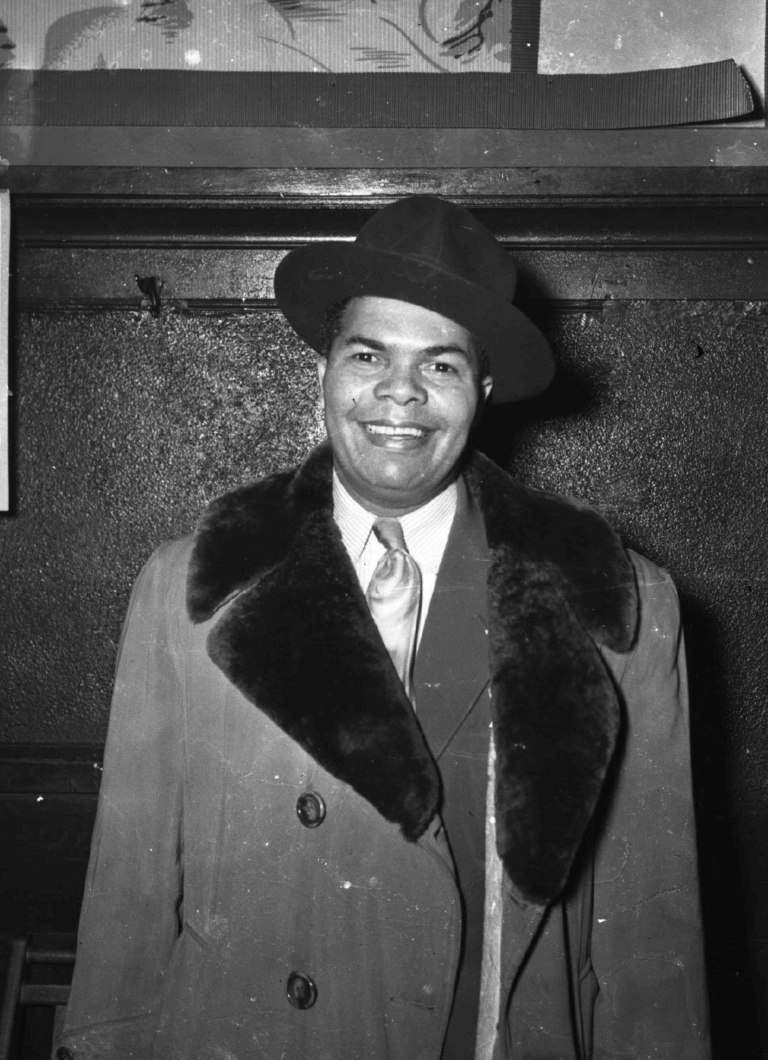

Dreamland Cafe

“The Dreamland Club opened on December 15, 1939 and was owned by A. Brutus Cassius and Thel Collins. Current addresses are 3759 (built in 1900) or 3753 (built in 1920).” Link

“In segregated Minneapolis, no Black people were welcome in downtown restaurants or hotels, including touring musicians or other celebrities who came to entertain white audiences. So they went to the Dreamland, and then private homes in the area, to sleep, eat, drink, and play. Lena Horne and Frankie Lymon famously visited the café. The Dreamland truly was just that—a place where people could don a sleek fedora, clutch a beer glass, be safe, and relax long enough to dream. Maybe of a better place—a place where the insidious tentacles of “Jim Crow of the North” could not slither in to stifle and choke.” Link

“But the Dreamland was more than just a place to eat dinner. “The Dreamland,” neighborhood activist Nelson Peery remembered, “was our only social center.” A rare public space that welcomed people of all races at a time when the city was rigidly segregated, it laid the foundation for social change. Cassius “always conducted himself as if he were responsible to and for the people in our neighborhood,” Peery recalled in his autobiography. “Concerned about the Negro people, always contributing to some cause, Mr. Cassius was the first ‘race man’ I met.” Cassius’ establishment welcomed young talkers and dreamers like Peery, who would spend his life working for social justice and civil rights.” Link

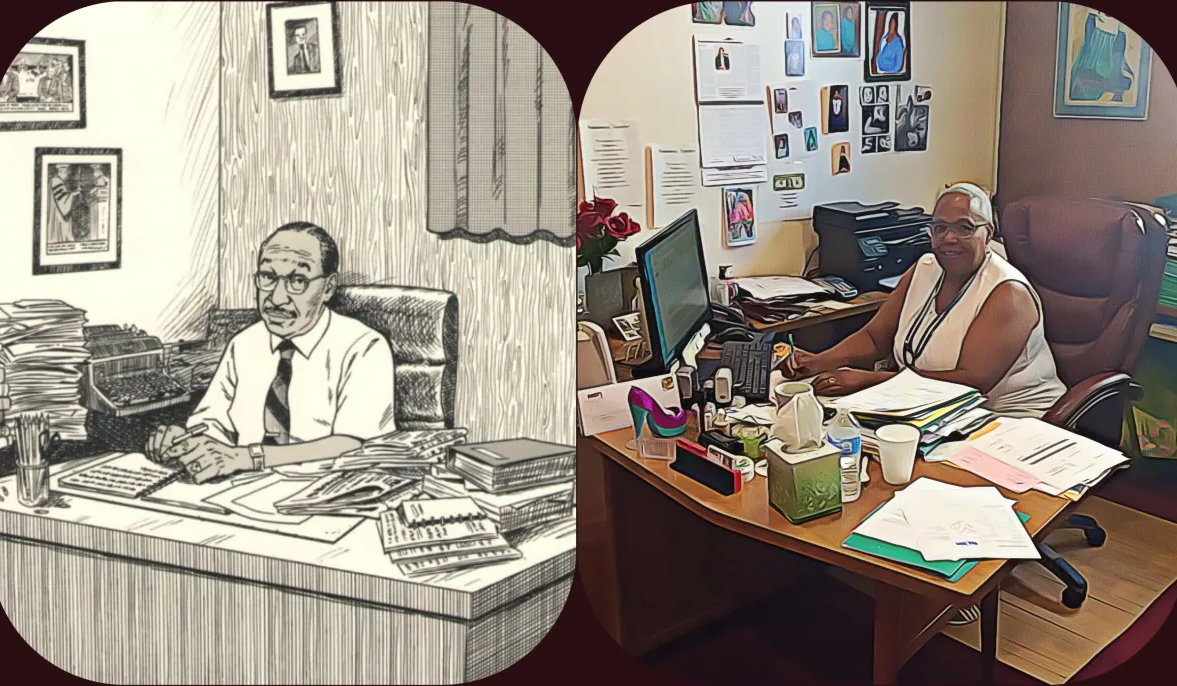

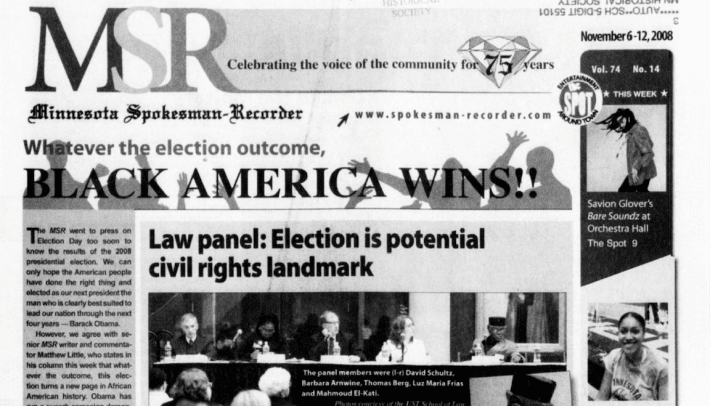

Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder

3744, 44th Avenue South

“The Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder (MSR) enjoys a living legacy as the oldest Black-owned newspaper in the state of Minnesota and one of the longest-standing, family-owned newspapers in the country.

Civil rights activist and businessman Cecil E. Newman launched the MSR in August 1934 as two separate papers: the Minneapolis Spokesman and the St. Paul Recorder before it merged into one single news publication in 2007. Today, the MSR is helmed by his granddaughter, Tracey Williams-Dillard, who serves as CEO/Publisher.

For the past 89 years, the MSR has established itself as a trusted voice for the diverse Black communities of Minnesota–championing voices and stories that might otherwise go unheard. Each week, the newspaper’s diverse staff creates original content for its print publication, along with daily content for its website that speaks to stories of human interest from a Black perspective.

More than just a newspaper, this includes creating content that not just informs, but also inspires, educates, and encourages conversations that go beyond today’s news headlines.

The MSR has expanded its reach via social and digital media channels, while also developing opportunities for community engagement and involvement via strategic partnerships and events.

In addition to serving as a trusted source for Black news and information, the paper is also a cherished cultural resource. The MSR building became a historic landmark on November 20, 2015.” Link

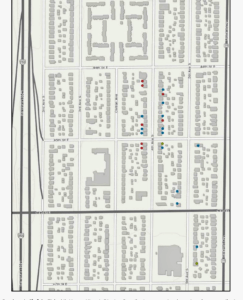

Tilsenbilt Homes

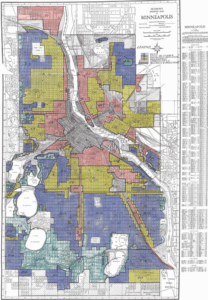

“Beginning with the New Deal in the Great Depression, the Federal Housing Administration and the Veterans Administration encouraged redlining and racial/ethnic covenants to enforce housing segregation. In Minneapolis, with cooperation among realtors, banks, and local governments, African-Americans were restricted to only a few neighborhoods, including the area centering around the corner of E. 38th St. and 4th Ave. So. Of nearly 10,000 single-family homes and duplexes built in Minneapolis between 1946 and 1952, fewer than 20 were sold to African-Americans.

Jewish home builder Edward Tilsen and African-American realtor/philanthropist Archie Givens broke that mold. They created what was probably the nation’s first federally-supported residential housing development open to all races. Between 1954 and 1956, with financing arranged by Givens, Tilsenbilt Homes, Inc. built 53 homes, many of which were located south of 42nd St. in a neighborhood that previously had been nearly all white. About 90% of those homes were sold to African-American or mixed-race buyers. In 2017, the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission designated the Tilsenbilt Home Historic District. Examples in the district include these addresses on 5th Ave. So.: 4004, 4012, 4016, 4021, 4025, 4028, and 4044.” Link

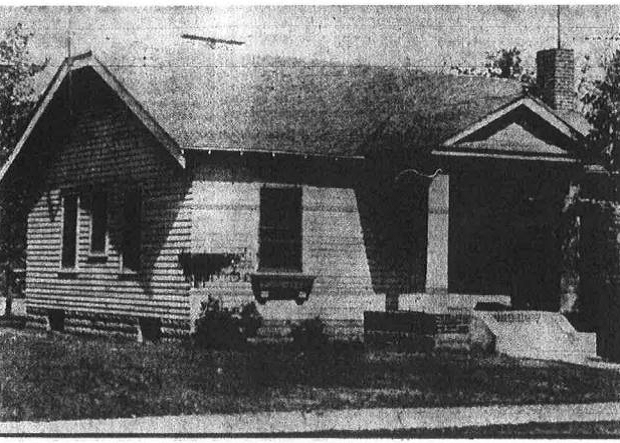

Arthur and Edith Lee House

4600 Columbus Avenue South

“Nobody asked me to move out when I was in France fighting in mud and water for this country. I came out here to make this house my home. I have a right to establish a home.”

“In the spring of 1931, Arthur and Edith Lee purchased a home at 4600 Columbus Avenue South in Minneapolis, where they intended to live with their daughter Mary. Area homeowners thought they lived in a “white neighborhood”. Many wanted the Lees to move. Neighbors offered to buy the property from the Lees for an inflated price. When the family refused, vandals threw garbage and human waste at the property; black paint was splattered across the house and garage; signs were posted on the lawn proclaiming “No niggers allowed in the neighborhood. This means you.” People began walking by the Lee house in the evenings yelling taunts and racial slurs. Conflict at the Lee house quickly escalated. On July 11th, around 150 people gathered on the lawn to protest. Five days later, the crowd had grown to 4,000. Some came from as far away as Hibbing to participate in what newspapers described as a “mob” and a “Minneapolis Riot”.

Histories Of Systemic Racism

35 W

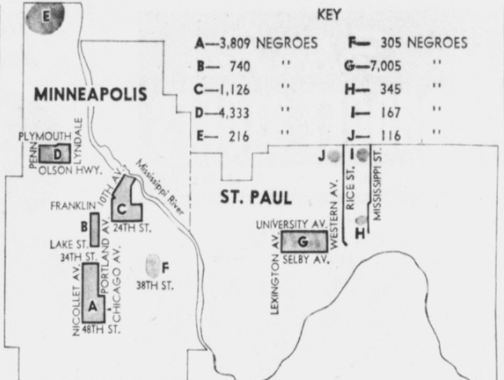

“The slice of the city between Nicollet and Chicago avenues, with 38th Street to the north and 46th Street to the south, was the hub of the black community in South Minneapolis, known as the Old Southside. It was one of the few parts of the city where black residents were able to own and rent their homes.

Construction began on the I-35W corridor in South Minneapolis in 1959 when the Minnesota Department of Highways began demolishing more than 50 square blocks of homes and businesses. Planners and engineers decided the route the freeway would take. Residents in the area were not involved in the decision making process and “policy makers ignored the existence of an integrated neighborhood/community during their planning.

I-35W plowed through the heart of the Southside black community. Residents of the area later interviewed said that the design of Interstate 35W, including the design and location of entrance ramps, exit ramps, and bridges significantly “split and divided the community” and that “the routing had the cumulative effect of segregating the schools and creating a barrier between those on the east and west sides of the freeway.”

Redlining and Racial Covenants

“4th Avenue was a line. It was an undesignated, well-understood line. People of color lived on the east side of 4th Ave, and white people lived on the west side of 4th Ave. As I recall, that’s pretty much how it was. Unspoken but clear.

Policies encouraging racial housing discrimination were rampant throughout the 20th century. In the early 1900s, race wars popped up across Minneapolis. White homeowners felt increasingly threatened by the presence of black families in their neighborhoods. By 1910, the first racial covenant appeared in Minneapolis, barring anyone who wasn’t white from owning or occupying property. Covenants spread like wildfire throughout Minneapolis, St. Paul, and the surrounding suburbs for decades, limiting access to housing for people of color.

Compounding the issue of racial covenants, real estate steering, in which realtors “steered” black homebuyers into established Black neighborhoods, ensured that communities of color had little chance of integrating into white neighborhoods.

Redlining in the 1930s further devalued many neighborhoods where people of color could live. The Old Southside black community was one of the few integrated areas that existed for communities of color in the city.” Link

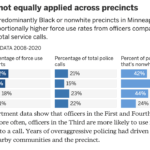

City of Minneapolis

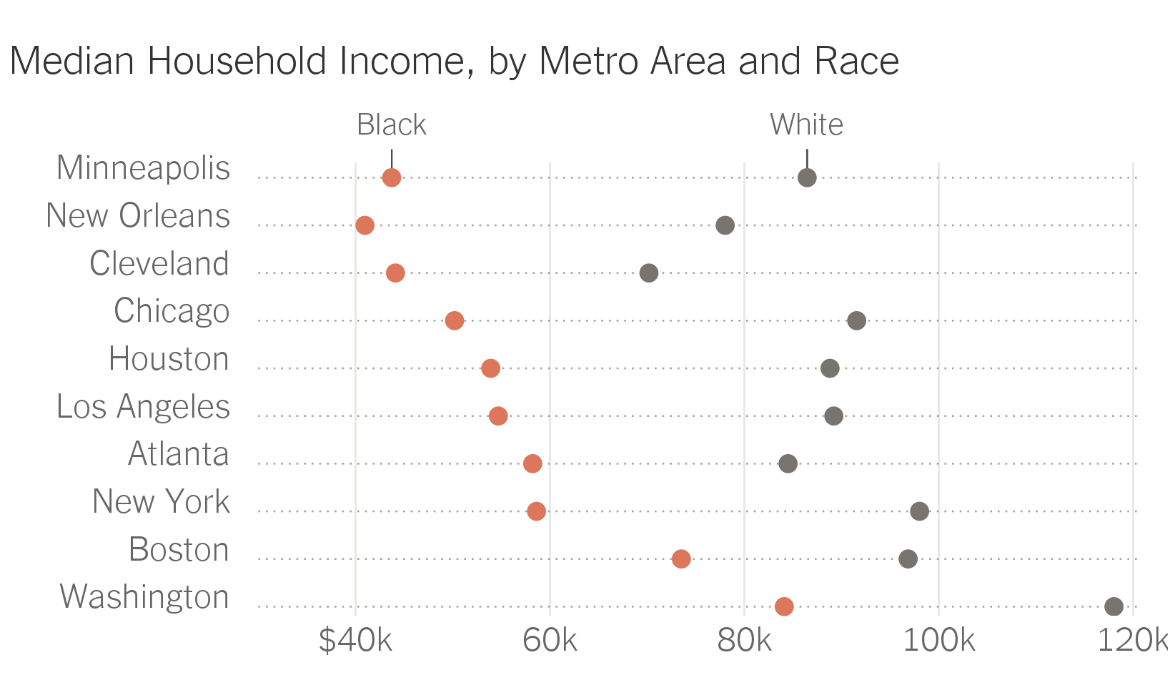

“Minnesota is one of the best places to live in America. It regularly produces some of the highest average scores in the nation on the SAT exams and boasts a disproportionate share of Rhodes Scholars and admissions to MIT and Harvard. The famed Mayo Clinic is an international leader in medical research and development of vaccines for critical diseases such as COVID-19. Housing prices are considerably below the national median, shopping is a delight at one of North America’s largest indoor shopping malls.

It nurtures a large and vibrant arts, theater, and music community, and was home to both Prince and Judy Garland. Good schools. Excellent housing. A strong regional transportation network. Excellent employers like 3M, Best Buy, Cargill, General Mills, Target, and US Bank contribute to a sustained and vigorous corporate giving culture where nonprofits are some of the best known in America.

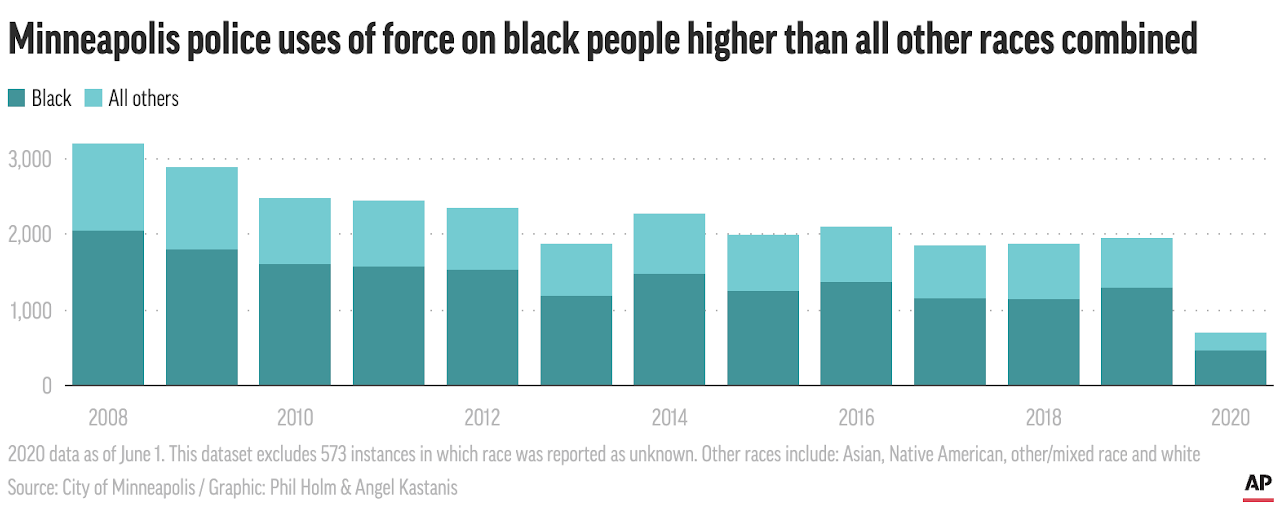

Surprisingly, Minnesota is also putatively one of the worst places for blacks to live. Measured by racial gaps in unemployment rates, wage and salary incomes, incarceration rates, arrest rates, home ownership rates, mortgage lending rates, test scores, reported child maltreatment rates, school disciplinary and suspension rates, and even drowning rates, African Americans are worse off in Minnesota than they are in virtually every other state in the nation.

The simultaneous existence of Minnesota as the best state to live in, but the worst state to live in for blacks, is the crux of “The Minnesota Paradox.”

38th Street Thrive

Over 20+ years ago, I, along with our former State Senator Jeff Hayden, the current Director of the Neighborhood and Community Relations department at the City of Minneapolis, and several others, started a Community Development Corporation called the Minnesota Renaissance Initiative. We formed to bring structure, resources, and help build wealth in the African American community. The first project area we started was 38th Street and Chicago Avenue. We selected this area because we knew that it was a historically Black community. It was the “Soul of the City.”

E. 38th Street continues to play a significant role in the history of the City of Minneapolis. On May 25th, 2020, the intersection of 38th and Chicago was rocked by the death of George Floyd at the hands of four former Minneapolis Police officers. The tragic events of the day will forever be acknowledged and memorialized, as Chicago Ave will be commemoratively named “George Perry Floyd, Jr. Place,” from 37th to 39th Street. However, the most fitting lasting legacy would be to ignite and support Black business ownership, and the creation of job training programs and opportunities for Black and Brown youth. We need a cultural institution, i.e. museum and gallery, that will lift up and preserve the contributions of African Americans in this community and beyond. A place to reflect, learn, heal, and grow. That is the vision of the 38th Street Thrive! Strategic Development Plan. Rest assured that the intersection of 38th and Chicago will have and deserves its own community process aside from the plans laid out here.